Plymouth’s Lighthouse History

OM Magazine, Issue 101, June 2017

26th May 2017

Operation Henry- Pancreatic Cancer Charity

31st May 2017Everyone knows of the iconic Smeaton’s Tower standing proud on Plymouth Hoe, but did you know that it is the third of four Eddystone Lighthouses? These impressive structures served as a beacon of safety for passing ships to avoid the treacherous reef below

The Eddystone, or Eddystone Rocks forms part of an extensive reef of eroded rocks which rise up in deep water about 14 miles South West of Plymouth. Formerly a treacherous hazard for ships approaching the English Channel and the port city of Plymouth, the rocks have played host to four generations of the Eddystone Lighthouse. What can be seen today is the fourth version of the lighthouse- Douglass’s Tower. Next to this, the stump from the third generation, Smeaton’s Tower still stands.

The Eddystone Lighthouse was the first lighthouse to be built on a small group of rocks in open sea and resulted in a few disasters until the present lighthouse which stands there today. Given the harsh surrounding these early lighthouses where considered a marvel of ingenuity.

1. WINSTANLEY’S TOWER 1698 – 1703

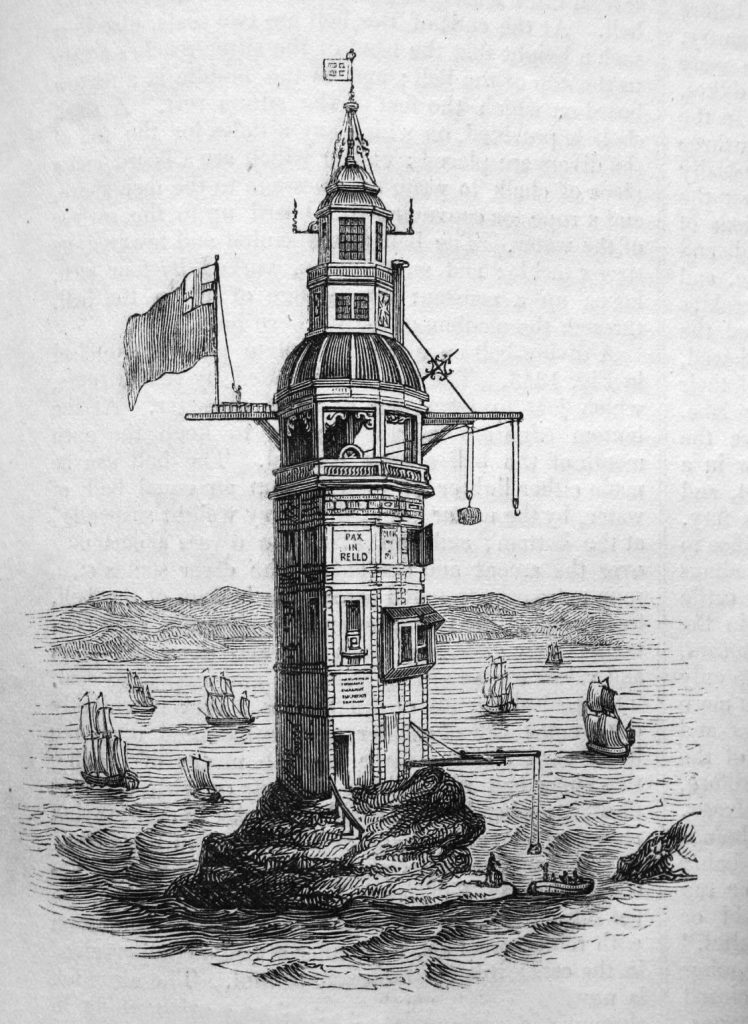

The first tower attempt to render the Eddystone Reef of rocks safe to shipping was by a man named Henry Winstanley, an engraver, merchant ship owner, and designer. Winstanley promised to rid the English Channel of such a menace to shipping after one of the ships he had invested in heavily was destroyed by the Eddystone Rocks.

In 1696, Winstanley commenced work on the octagonal wooden structure. The work progressed steadily until 1697 when an incident occurred in which a French privateer captured Winstanley and took him to France. England was at war with France at this time. However, when Louis XIV heard of the incident he immediately ordered that Winstanley be released saying that “France was at war with England,not with humanity”. This rendered the importance of the Eddystone International.

The light in the Eddytone was first lit in 1698. 24 candles were used in total and it was the first offshore lighthouse to be built in Britain. Winstanley was known as an eccentric, and this was reflected in his architecture. External ladders, a huge weather vane and ornamental scroll work adorned the exterior of the huge structure.

Having great confidence in his structure Winstanley expressed a wish to be on the lighthouse during a storm. In November 1703, the greatest storm ever recorded in this country occurred. The following day there was hardly any of the lighthouse structure to be seen and its occupants had disappeared. The lighthouse had survived only three years.

Just two days after the tragedy the tobacco ship, ‘Winchelsea’, was wrecked on the reef, but it would be another three years before someone was appointed to design a new lighthouse.

2. RUDYERD’S TOWER 1709 – 1755

2. RUDYERD’S TOWER 1709 – 1755

Captain Lovett acquired the lease of the rock for 99 years, and by an Act of Parliament was allowed to charge all ships passing, a toll of 1d per ton, both inward and outward. His designer was John Rudyerd, a London based silk merchant with West Country roots, who he engaged to design and build a new lighthouse for the Eddystone reef in 1706.

Taking a shipbuilders- rather than a house builders, approach he came up with a design based on a cone instead of Winstanley’s octagonal shape. He built a conical wooden structure around a core of brick and concrete and it was first lit in 1709.

This design was solid and the lighthouse lasted for 47 years, until it was destroyed not by the sea, but by a fire. In 1755, the top of the lantern caught fire. Henry Hall, the keeper on watch, who was 94 years old (some accounts say 84 years old) did his best to put out the fire by throwing water upwards from a bucket.

While doing so, the leaden roof melted, and molten lead ran down his throat as he was looking up. He and the other keepers battled continuously against the fire, but as it burnt downwards it gradually drove them out onto the rock. The lighthouse continued to burn for 5 days and was completely destroyed.

Sadly, Henry lived only 12 days after the incident. The piece of lead found in Henry Halls stomach after post Mortem can still be seen today in the Edinburgh Museum.

3. SMEATON’S TOWER 1759 – 1882

Smeaton’s Tower- the third lighthouse, marked a major step forward in the design of such structures. For the first time on this site was the work of a leader in the civil engineering profession of his time. After experiencing the benefit of a light for 52 years, mariners were anxious to have it replaced as soon as possible.

In 1756, a Yorkshire man and civil engineer named John Smeaton, who had been recommended by the Royal Society, travelled to Plymouth to take on this task. He had decided to construct a tower based on the shape of an English Oak tree for strength but made of granite blocks rather than wood. The lighthouse had a slightly curved profile, which strengthened the structure and gave it a low centre of gravity.

John Smeaton pioneered ‘hydraulic lime’, a quick drying concrete that will set under water, the formula for which is still used today. He also developed a technique of securing the granite blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. He is also credited with coming up with a device for lifting large blocks of stone from ships at sea to considerable heights which has never been improved upon.

Local granite blocks was used for both the foundations and exterior of his tower, and Portland stone for the inside. Construction started in 1756 at Millbay and the light was first lit by 24 candles on 16 October 1759. Smeaton’s robust tower set the pattern for a new era of lighthouse construction.

In the 1870’s cracks appeared in the rock upon which Smeaton’s lighthouse had stood for 120 years. It was also by this time, too small to contain the latest machinery. It was re-erected on Plymouth Hoe as a monument to the builder and has been Plymouth’s most famous landmark ever since.

4. DOUGLASS’S TOWER – 1882 ONWARDS

Because the move of Smeaton’s Tower was pre-determined, a replacement lighthouse was able to be planned quickly. The new larger tower, 49 metres high, was designed by James Douglass, at the time Engineer-in-Chief of Trinity House. It was founded on the actual body of the Eddystone reef some 40 yards to the south-east of Smeaton’s site.

By now, lighthouse construction was a much more refined business due to the developments made throughout the years.

Douglass used larger stones, dovetailed not only to each other on all sides but also to the courses above and below. It was completed in three and a half years, and in 1882 the present Eddystone Lighthouse was opened amidst a blaze of publicity, by the Duke of Edinburgh, who laid the final stone of the tower.

Douglass Towers original oil powered lamps were replaced by electrics in the 1950’s, and a helicopter deck was constructed in 1980. Another part of the modernisation process was the lighthouse becoming unmanned in 1982, bringing an end to the 284 years of keepers of the Eddystone Light.